On Your Next Trip to

Nepal, Rent the House Sir

Edmund Hillary Loved

On Your Next Trip to

Nepal, Rent the House Sir

Edmund Hillary Loved

THE SO-CALLED HAPPY HOUSE IS WHERE THE

EVEREST CONQUEROR USED TO STAY ON HIS RETURN

VISITS TO THE HIMALAYAS. NOW RUN BY THE SHERPA

FAMILY WHO BUILT IT, THE HOUSE CAN BE TAKEN

OVER FOR ADVENTURES OF YOUR OWN.

December 20, 2018

This journey begins with the helicopter flight out of Kathmandu. The mountains rise in narrow wedges; pine trees cling to the ridgelines, their contours drawn by lime-green terraces and crops cut into bobble-headed bushels straight out of Dr. Seuss. Within an hour—in air so clean you can see all the way to Everest—I’m in Phaplu, the cradle of Sherpa culture. Turn left from the village airstrip and it’s a three-day hike to Lukla, the gateway for Everest climbs. Turn right, and it’s a five-minute walk to the Happy House.

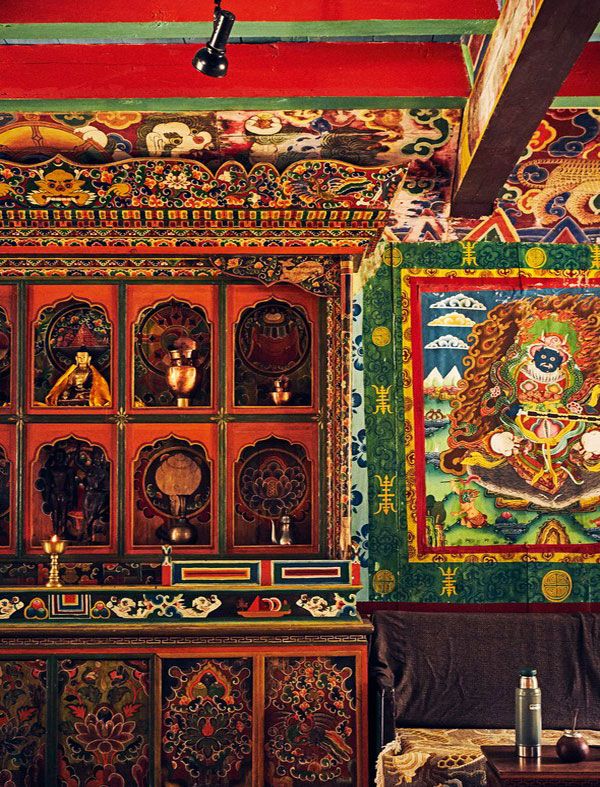

Up a flight of stone steps, beneath fluttering prayer flags, the house stands on a wide terrace flanked by moody pines. Inside, the walls of the main room are painted in the madder reds of a monk’s robes. In the shadows, a dragon with a polka-dot tail lashes at the rafters, while blue-faced Tibetan demons grimace, their goggle-eyes yellowed by smoke. These frescoes were begun in 1974 by Khapa Rinzi, a Sherpa master of the monastic art of thangka painting.

In Buddhist culture, both creating and looking at a thangka are acts of meditation, which gets to the heart of how it feels to sleep here—a private home in the Himalayas, now renovated into a house to rent. Soon after it was finished, Sir Edmund Hillary stayed here, and continued to do so until 2001, when he stopped coming to the Himalayas (he died in New Zealand in 2008). His affection for Phaplu gave the Happy House its name. Hillary came because of a hospital he founded in 1975 to serve the remote valleys of the Solukhumbu, still just five minutes down the road.

Yet it wasn’t Hillary who built the home, but another Everest expeditionary: a debonair, mustached Italian named Count Guido Monzino. From 1955 to 1973, Monzino adventured from Senegal to the North Pole, from the Tibesti plateau in Chad to East Africa’s Mountains of the Moon. In 1973, he led the first Italian expedition to climb Mount Everest in what was heralded as the most extravagant attempt of all time: 6,000 porters, whose luggage included fine wines, cigars, silver cutlery, and an English leather sofa, which now rests beside the fire where I am sitting.

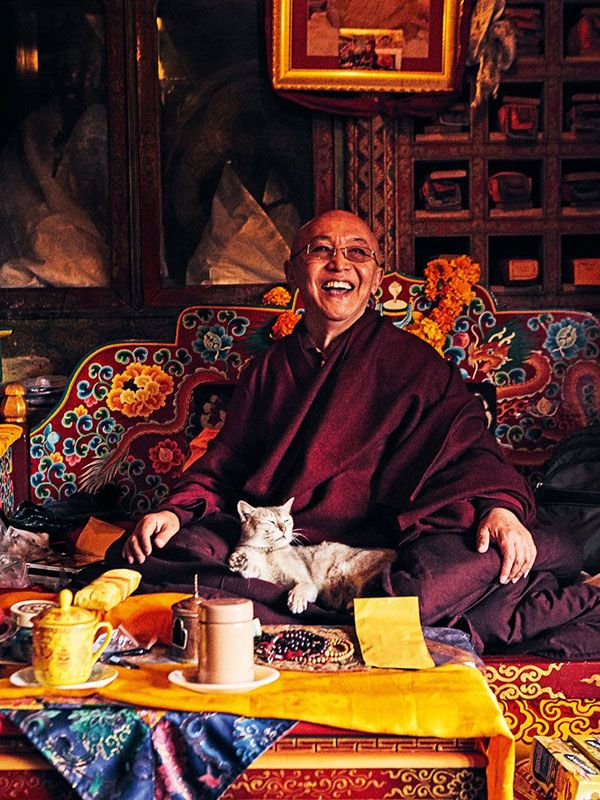

Also among the count’s climbing party was Rinzi Pasang Lama—the patriarch of a high-profile Sherpa family; he was the great-great-grandson of the founder of Chiwong Monastery, which clings to a cliff at the valley’s back. When he was 18, R.P., as he’s known, helped build the Happy House on his family land under the guidance of Monzino, who paid for the construction. In the house’s early days, the odd mountaineer stopped by this Hostellerie des Sherpas. “Monzino always brought interesting people—he was a generous, elegant man,” recalls R.P., now 63. On the count’s death, in 1988, R.P.’s family operated it as a modest guesthouse, only to see this eccentric legacy be almost lost forever due to Nepal’s political tumult.

In 1996, a violent Communist insurgency ravaged the country; over the next 10 years, some 17,000 people were killed, with civil war finally putting an end to the incumbent government and 240 years of the troubled Nepali monarchy. On a dark winter’s night in November 2001, R.P. hid on the grounds of the Happy House while 35 government officials were shot dead in a rampage that would be the biggest battle of the Nepalese civil war. Twelve days later, R.P. left Nepal with his family, taking $10,000 and a single suitcase from Phaplu. They were given political asylum in the U.S. and settled in Queens, New York, where they opened a grocery.

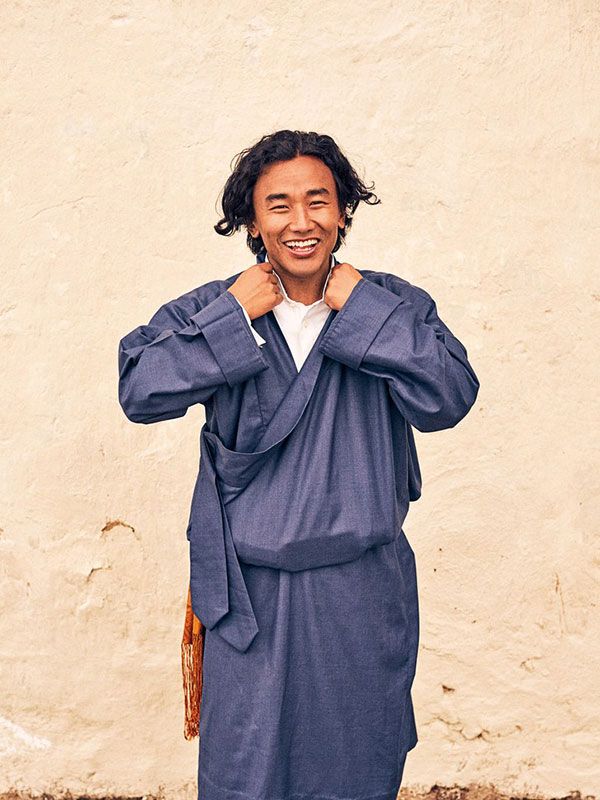

The Happy House could have been lost forever in that turbulence. Instead, R.P. handed it over to a German filmmaker, Christopher Giercke, who had been coming to the valley since the 1980s to make a movie, Lord of the Dance: Destroyer of Illusion. Giercke kept the spirit of the house intact, visiting it often with friends—including my family—until the summer of 2017, when R.P. and his son, Ang Tshering Lama, decided to invest in the home’s renovation. This fall, it opened as the hub of Ang’s new travel company, Beyul Experiences. “In Buddhist texts, a beyul means a sacred space, like Shambhala,” he says. “I’ve always thought of this family home as the paradise of my early childhood.”

The Happy House can’t help but seduce, even if (or because) it doesn’t have the nickel-tapped polish of a luxury hotel. Once when I visited, the British adventurer Levison Wood was walking the Himalayas for his hit television series and ended up staying here. “A sort of salon for the mountain literati,” he described it later, “packed with history against the backdrop of the magnificent Himalaya.” On my most recent visit, the British novelist Laura Beatty was staying too. When she emerged from a two-hour healing session with Sugam, the home’s craniosacral therapist, she said, “Something just happened I can’t put into words.”